Despite great progress across two centuries, exclusion and injustice remain the reality for too many black Americans

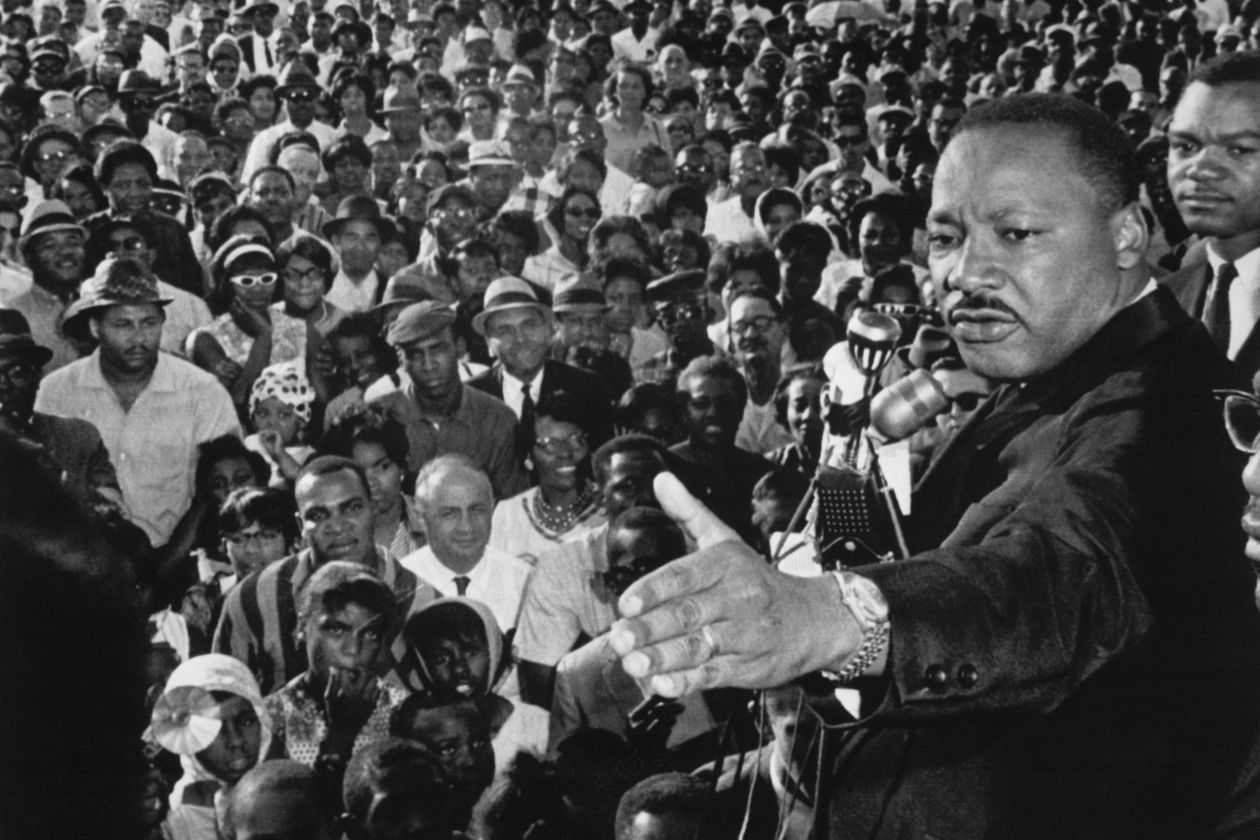

One of the many ways, good and bad, in which America is truly exceptional is its experience of race—its tortured embrace of black Americans and the paradoxical extremes in how it treats them. Race is the fulcrum upon which two radically different visions of America pivot. In the inhuman, banal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis we see the reactivated weight of the country’s darkest past. In the nationwide demonstration of young blacks and whites against it and other recent racist killings, we see the outraged, countervailing force of that other America which Martin Luther King Jr. imagined as the “beloved community.”

The despair of so many Americans in this moment of naked exposure of racism’s persistence in the U.S. should not lead us to deny the successes of the civil rights revolution. Black Americans are now included in the public domain of the nation. They form an integral part of its political life and an important component of its military, and they play an outsize role in its intellectual and cultural life. The black middle class is real, however tenuous its economic base and downwardly mobile its male children. The majority of white Americans have also undergone a radical transformation in their racial views, especially the young, who are arguably the most racially liberal group of whites anywhere in the world.

But the civil-rights movement failed to integrate black Americans into the private domain of American life. American communities and schools remain highly segregated. Measures of segregation at the metropolitan level have declined in some cities but remain high, and cities such as Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee have become far more segregated. Moreover, as Daniel Lichter of Cornell University and his co-authors show in a 2015 paper in the American Sociological Review, once we move down to the level to the neighborhoods where people actually meet and interact, there has been little or no change in the degree of separation of black and white families, and segregation between cities and suburbs has gotten worse.

Between 1985 and 2000, a higher percentage of black children—about two-thirds—grew up in high-poverty segregated areas than in the period between 1955 and 1970, according to a 2009 Pew Trust study by the sociologist Patrick Sharkey of New York University. This not only influences the kind of schools they attend but all the other major factors accounting for their social mobility and life chances, such as health and life expectancy. Today the majority of black kids, including those from upper middle class families, experience downward mobility.

Orlando Patterson – The Wall Street Journal – June 5, 2020.